How did Scoville access Patient HM's medial temporal lobe?

(I write more about Patient HM and his brain surgery in my book Horror on the Brain. This was a wonderfully insightful question that one of my students asked halfway through a lecture describing Patient HM, the patient and case study from whom much of our modern understanding of the types of memory came from. I was immensely impressed with the student who considered the logistics of the surgical process during the temporal lobe removal.)

A common case study taught during “Introduction to Neuroscience” courses, the clinical description of Patient HM is one of the most intriguing in the literature.

Patient HM, born in 1926, suffered from intractable epilepsy, likely the result of a head injury early in his life. His epilepsy was debilitating, as he was frequently admitted to the hospital for grand mal seizures. Anti-epileptic medications weren’t working for him, and the severity and frequency of his seizures continued to get worse as he reached his twenties.

Desperate for relief, HM and his family sought the advice of a prominent neurosurgeon, William Beecher Scoville, then based at Hartford Hospital in Connecticut. And in 1953, HM went in for radical brain surgery: bilateral medial temporal lobectomy with a focus on removal of the hippocampus, the brain structure where HM’s epileptic seizures originated.

Patient HM in 1953. Taken from Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25399602

When the wounds had been sutured, HM discovered that Scoville’s procedure was successful in it’s primary objective. He experienced far fewer seizures than before, and whenever they did happen, they were significantly less severe.

However, the removal of these critical brain areas left HM with a profound deficit: He was unable to create new memories.

Much of the neuropsychological testing performed on HM was done by Drs. Brenda Milner and Suzanne Corkin. They found that, several years after his surgery, HM was unable to recall events from his own life (such as what he had done yesterday, or even an hour ago), unable to identify new words that have come into popularity since his surgery (such as “granola” or “psychedelic”), and unable to recognize celebrities who became famous since his surgery (like Carrie Fisher). Milner and Corkin described these types of memories as declarative memories.

However, not all of HM’s memories were wiped clean. He had a perfectly intact declarative memory for things that happened early in his life, prior to the surgery. He could remember short pieces of information temporarily, like a phone number. He could also learn complex motor tasks, such as tracing a star while only watching his hand in the mirror, a type of memory called an implicit memory. (Many of HM’s deficits were described brilliantly by Dr. Corkin in her book Permanent Present Tense.)

Patient HM died at the age of 82 in 2008. Because of Henry Gustav Molaison’s surgery and subsequent amnesia, neuroscientists and psychologists have learned a tremendous deal about memory.

So how did Dr. Scoville access HM’s medial temporal lobe?

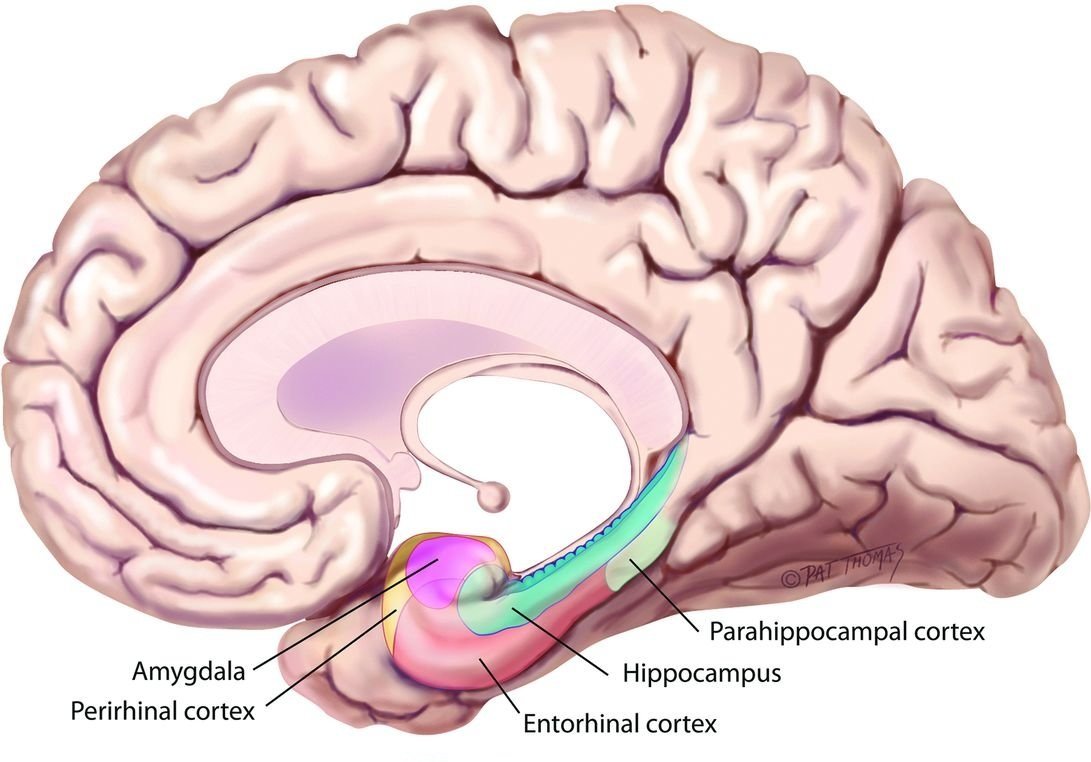

If I were Dr. Scoville looking to remove a part of HM’s cortex, the medial temporal lobe and the hippocampus might be the toughest target to reach physically. Take a look at where this brain structure is located, highlighted in light green:

Taken from http://www.ajnr.org/content/ajnr/36/5/846/F1.large.jpg?width=800&height=600&carousel=1

This image shows a medial view of the brain, as if you were to split the left and the right hemispheres apart. The hippocampus is buried deep within the brain, making it very difficult to access with tools.

I have to admit, I never thought about this question before. My first thought would be to go from the dorsal surface, like I might do if I was doing stereotaxic surgery on a rodent. But going from the top of the brain all the way into the more insulated areas would cause a lot of damage, as tissue would get pushed aside or stretched unnaturally, resulting in untold cellular destruction of areas not associated with HM’s epilepsy.

Obviously, my approach would be a terrible mistake. Instead, I’ll let Scoville do the talking:

"Bilateral supra-orbital one and one-half inch trephine holes provided access to the temporal lobes"1

Supra-orbital = above the orbit of the eyes

Trephine = holes through the skin and skull

In other words, they drilled two holes in HM’s forehead.

Image taken from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-illustrations-of-the-supraorbital-keyhole-a-and-lateral-supraorbital-keyhole_fig2_262816738