How a vestibular injury made Tyson Fury the lineal heavyweight boxing champion

In one corner was Deontay Wilder, weighing in at 231 pounds and standing six feet seven inches tall. While an amateur boxer, Wilder represented the United States in the 2008 Olympics, earning himself a bronze medal, which gave him the nickname “The Bronze Bomber”. And as a professional, Wilder had won 42 of his fights, 41 of them by knockout, many by means of his devastating right hook. He was the reigning WBC champion, and had a lot on the line in this fight.

Across him stood Tyson Fury, intimidating at 273 pounds on a six feet nine inch frame. Nicknamed the “Gypsy King”, Fury himself had several heavyweight titles and the massive, gleaming belts to prove it. Fury was known for his antics in the ring and out, making mocking faces to his opponents and even randomly breaking out into song after the match.

These two rivals had faced each other before, just a year prior to the big sequel fight. However, both fighters were still undefeated - their first faceoff had ended in a controversial split decision, prompting the 2020 rematch at the MGM Grand. Although the $25 million dollars to be made by each competitor was a big motivator, the heavyweight title was on the line, which would rank the victor among the greatest in the sport.

The first two rounds had more action than you might expect early in a big fight, as the pugilists clearly had Unfinished Business to settle. Late in round three, Fury downed Wilder with a massive right hook.

After the round, Wilder’s corner wiped away blood from his left ear. From then on, it was clear that Wilder was in trouble. He slipped twice in the following rounds, and after getting knocked down again in round five, his corner threw in the towel in the seventh round.

Fury’s massive shot to Wilder’s right ear was largely to blame for Wilder’s poor stability. His legs were unsteady underneath him, as if he had just stepped off a Tilt-a-whirl and onto a rocking boat on the stormy ocean.

At the beginning of the fight, a series of neural structures buried deep within the inner ear were responsible for helping Wilder process the sensations of up to down, forward to back, and left to right. These structures are called the vestibular system, and they communicate with other structures in the brain to help him maintain his balance.

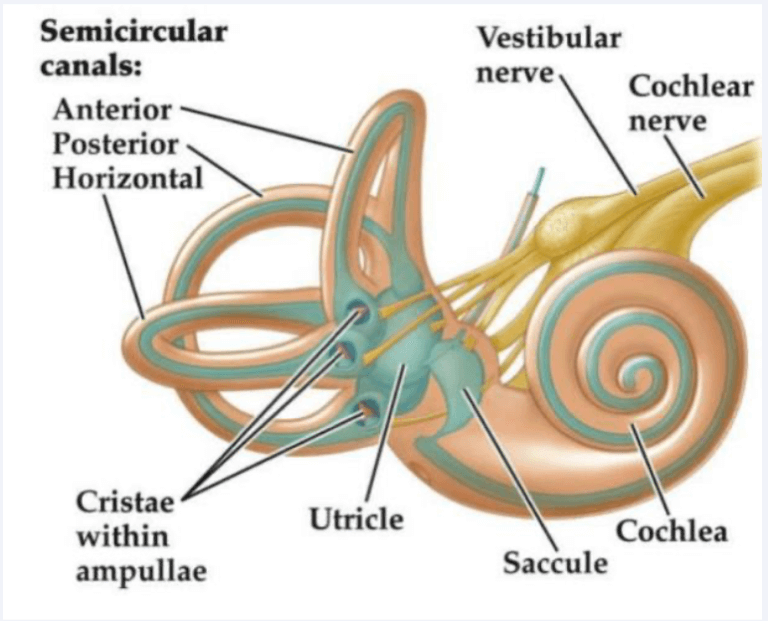

One major component of the vestibular system is a set of three curved membranous tubes called the semicircular canals. These tubes are oriented at 90 degrees to each other, and are filled with a fluid called endolymph. At the end of each tube is a population of neurons called hair cells. These cells send signals to the brain through the vestibulocochlear nerve, sometimes also called cranial nerve VIII. This signaling is responsible for conveying information about head tilt and rotation.

When the head tilts in a specific direction, the endolymph will flow towards the end of a particular semicircular canal. That physical movement causes a change in the activity of the hair cells, causing them to send more signals through the vestibulocochlear nerve. Simultaneously, the endolymph in the other two semicircular canals moves differently in response to the same head tilt, causing those other hair cells to also change activity. These pattern changes are decoded by structures in the brain, particularly the brain stem and cerebellum, which then inform other parts of the brain about how the head is tilted.

Imagine you are being hit by an uppercut to the chin or a jab to the forehead, causing your head to tilt upwards (the safer alternative is to look up at the ceiling). In this case, the hair cells of the superior semicircular canal will change the most as the endolymph rushes to the end of this canal. Later in the fight, you are hit with a hook to the cheek (or, you shake your head sideways to indicate “no”), twisting your head to the side. This head movement information is conveyed by the hair cells of the horizontal semicircular canal. Then, you get caught with a hook to the chin, twisting your head and bringing your ear towards your shoulder. In this case, the hair cells of the posterior semicircular canal sense the displacement.

Direct trauma that affects these structures, as Wilder suffered in the third round, could lead to difficulties with processing vestibular information. It is difficult to describe exactly what Wilder experienced as he struggled to hold on in the fight. Vertigo, or the sensation of movement when none exists, is a common vestibular symptom following traumatic brain injury. Disequilibium is the generalized loss of balance, a difficulty with keeping the body upright. Both of these conditions would lead to the shaky legs and the stumbles that we saw in the ring.

Without a complete clinical examination, it is also difficult to determine exactly what caused the injury to Wilder’s sense of balance. A sudden displacement of the head can cause a stretching of the delicate nerve fibers, which may prevent those normal “upright” signals from being sent properly into the brainstem. When this happens, there is now an imbalance in the signals, which might lead to a distorted sense of direction.

The blood trickling from the ear provides a different clue. The maxillary artery and the smaller branches that feed the outer ear are more vulnerable to damage from one of Fury’s punches. These are separate from the labyrinthine arteries that provide blood to the inner ear structures, like the semicircular canals and the vestibulocochlear nerve. It’s a bit unclear if the ruptured arteries led to some sort of alteration of healthy vestibular signaling.

All this should serve as a reminder of just how dangerous the sport of boxing can be. Competitors are acutely aware that despite hours of intensive training, they are putting their lives on the line every time they step into the ring.